Grant Opportunities List – 09.06.24

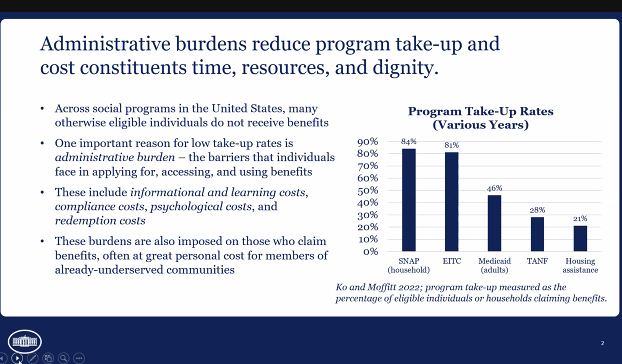

Yesterday, the White House presented a briefing on State and Local Administrative Burden Reduction. The slide below shows the main points made during the session. The Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs

(OIRA) will have a comprehensive webinar on these issues in the near future. Keep an eye on this site in case you are interested:

Information

and Regulatory Affairs | OMB | The White House.

Here are new opportunities from this week – noted in yellow in the spreadsheet. We also highlight in yellow any items listed or forecasted early where there are notable changes. We post new rolling opportunities

up top, then we move them to the last section with other rolling opportunities. Please note that all items are uploaded to the HANO Grants Corner Funding Opportunities list and can be searched via keyword:

Grants

Corner – Hawaiʻi

Alliance of Nonprofit Organizations (hano-hawaii.org).

The total amount from the competitions where we have program totals is almost $11 billion.

Hawaiʻi Specific or Native Hawaiian Focused:

- HHS Combating Hate and Promoting Healthy Communities Innovator Challenge (HHS and White House Initiative on Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders)

- Women’s Fund of Hawaii – Request for Proposals

- DOT NHTSA – Judicial Tools to Combat Impaired Driving

- ED OESE – College Assistance Migrant Program (CAMP)

- EPA – FY25 Guidelines for Brownfield Assessment Grants (Community-Wide Assessment Grants)

- EPA – FY25 Guidelines for Brownfield Assessment Grants (Assessment Coalition Grants)

- EPA – FY25 Guidelines for Brownfield Revolving Loan Fund Grants

- EPA – FY25 Guidelines for Brownfield Cleanup Grants

- DOI BOR – Small Surface Water and Groundwater Storage Projects (Small Storage Program)

- NEH – Digital Humanities Advancement Grants

- VA – Grants for Adaptive Sports Programs for Disabled Veterans and Members of the Armed Forces program – forecast

- VA – Grants for Adaptive Sports Programs for Disabled Veterans and Disabled Members of the Armed Forces (Equine Assisted Therapy) – forecast

- DOC NOAA – FY2024-2026 Broad Agency Announcement (BAA), Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research (OAR)

- Kyndryl Foundation – Request for Proposals

- Council on Library and Information Resources – Digitizing Hidden Special Collections & Archives

- US Conference of Catholic Bishops

- Community Development

- Economic Development

If you have any opportunities for consideration for future lists, please send them by noon on Thursdays. Also, let us know if you see any information that needs updating or correcting.

Happy Aloha Friday,

Melissa + Elijah

Melissa Unemori Hampe

Partner | Skog Rasmussen LLC

P.O. Box 2281, Wailuku, HI 96793

202-841-3368

Fred Baldwin Memorial Foundation grant supports outdoor service learning with seed storage and propagation

Maui Nui Botanical Gardens was granted $7,000 from the Fred Baldwin Memorial Foundation in support of high school and college student outdoor service learning in native Hawaiian seed storage and plant propagation. Garden staff will train and supervise volunteers in preparing wild collected seeds for drying and propagating native plants from the Garden’s plant collection. The public native plant garden manages a seed bank for Maui County native plant populations, which provides conservation land managers materials for research and future restoration. Space is limited; students enrolled in high school or college who are seeking volunteer experience required for graduation are encouraged to call Maui Nui Botanical Gardens at 808-249-2798.

Hawai’i Sheep and Goat Associations Film Imu Demonstration Video

Hawai’i State agricultural nonprofit, the Hawai’i Sheep and Goat Association teamed up with the Men of PA’A to stage and produce a unique imu demonstration video. Filmed on location in Puna District, Big Island, the video includes a step by step on how to build and utilize an imu. The video also highlights the use of local lamb cooked in the imu.

“In order to promote the production of local food and cooking techniques, we wanted to spotlight the use of Hawai’i grown, grass-fed lamb, using this ancient Hawaiian way of cooking,” said Julie LaTendresse, HSGA VP. “The video illustrates that all different types of food can be cooked in an imu.”

The Hawai’i Sheep & Goat Association is a 501 c 5 nonprofit whose mission is to support, improve, and strengthen Hawai’i’s sheep and goat community. We provide networking opportunities, coordinate educational and promotional events, and serve as a unified voice to represent island sheep and goat producers.

The organization received a promotional grant from the Hawai’i Department of Agriculture. With this grant, they were able to produce a local cookbook including recipes for cooking lamb and goat, as well as recipes utilizing milk, cheese and many local ingredients.

“In order to get people to eat locally we need to highlight great local foods and ways to cook that food.” said Amy Decker, a local goat farmer in Kona.

The video was filmed over three days and also highlights important Hawaiian knowledge and culture passed down from the ancient Hawaiians. The Executive Director of local nonprofit the Men of PA’A, Iopa Maunakea was the Kahu imu for the three days. He brought together all the parts and the knowledge passed down from his Kupuna to execute the imu.

“It’s important that we pass the food wisdom that was given to us by our ancestors. We want to teach our keiki how to do imu like it was taught to us. And by using local ingredients like sheep, kalo, sweet potatoes, we can try to pass on the importance of food independence and sovereignty for Hawai’i,” said Maunakea.

Post-Doctoral Researcher, Dr. Katie Kamelamela attended the imu and helps bring a larger context to the video.

“Doing imu is a Hawaiian cultural practice that combines not just ways of cooking food, but multiple rites of passage, as well as opportunities for people to come together to share food and stories.”

Chef Ellard Resignato, Executive Producer of the Hawai’i Island based food and travel TV/Web series the Culinary Edge TV filmed and edited the video. “This video brings together so many important elements like community, food knowledge, local food, cultural practices, and wisdom. It provides a window into the future of sustainability and food sovereignty on our island,” said Resignato.

The video will Premiere on the Hawai’i Sheep and Goat Associations YouTube channel on April 22 at 6:00 P.M.

Tropical Turkey Hunting

NewsDome –

Gobble Aloha –

Though I’ve been hunting birds for many many years, the chance to hunt a turkey had thus far eluded me until this year. Though there is turkey hunting in my home state, I live in a zone that holds so few birds that its closed to hunting. In order to hunt a turkey, its at least a 5 hour drive. That sort of time and fuel investment might be worth it for big game, perhaps, but not for a bird. Luckily, I had the opportunity to harvest some nice gobblers this year while on vacation in the land of aloha. You read that right: Tropical Turkey in Hawaii.

Struttin’ at the Beach

My first clue that there were game birds in Hawaii was about a decade ago. After doing some shore fishing, I was relaxing at a relatively deserted beach when I heard a gobble. I sat up and looked around, and sure enough, there was a group of tom Rio Grande turkeys chasing around a few hens! I watched them with amazement, and then asked a local what the deal was with the birds. He explained that they were brought to that particular area during the era of large pineapple plantations for hunting by the plantation owners, along with pheasants and other game birds. The tropical climate, abundance of roosts, plentiful forage, and relative lack of predators suited the turkeys well and they continue to flourish.

This year, I was introduced to a company called Hawaii Safaris. They take a lot of the busy work and headache out of hunting in Hawaii (if you’re just there for vacation, there’s a lot of logistics and paperwork to deal with including your firearm and desired hunting location), and offer different game and experiences on the islands of Hawaii, Maui, Molokai and Kauai. A local friend of mine on the “big island” heard that I never had hunted turkeys before, and hooked me up with one of their local turkey hunting guides for a two-bird hunt.

Morning Coffee

The morning of the hunt, we headed out in his truck to some hills above a massive Kona coffee plantation. The area where we were hunting was a balmy 60 degrees first thing in the morning. Coming from the Rockies, where I’m used to freezing in the early morning while hunting no matter the time of year, this was a pleasant change. Upon turning into the hunting area, we got out of the truck and immediately heard gobbling. The toms were out, and hopefully a few were not paired up with hens yet. We took cover behind some rocks, and my guide gave a few calls using a box call. The toms started to head our way, but then were distracted by a few real hens. After a while with no luck, we headed further on into the rolling meadows interspersed with Koa trees.

Our next setup was nearly a sure thing, but the interested toms ended up being scared off by (for me) an unexpected animal. Small herds of wild horses were moving around in the sunrise, and ended up scaring off our toms not once, but three different times! Ultimately, frustrated by all the horse commotion, we decided to head to a thicker, more overgrown area where the horses might not be, and the turkeys probably would be. On the edge of thick jungle, we took cover again behind a small rocky rise and started calling. The warm tropical air and the sound of Japanese white-eyes warbling from the jungle made for a somewhat surreal scene as a bunch of toms were gobbling and fighting over a hen. They were so busy taking turns knocking each other off the hen, gobbling and booming that they paid no mind to our calls.

Closing In

After about 25 minutes of waiting for the birds to come to us, we decided that I should slowly make my way over the rise and take a shot at the distracted toms. Crouching low, I made my way forward. The first tom that I saw 35 yards away had enough of his body occluded by large lava rocks that I couldn’t take a shot. I waited for him to strut into a draw, and then made my way quickly, but quietly to a point where I could fire into the depression. In the depression was not one, but six toms, all squabbling with each other. These birds were fired up! Raising up the borrowed 90’s era Remington 870 Express that I was using, I shot one tom who was off to the side of the gaggle. I waited for the clump of toms to disperse a bit, and shot one more once I had a clear shot at a specific bird. Two fine Rios were down, I could now get to the business of tasting tropical turkey!

Tropical Turkey, Hawaiian-style

After the excellent hunt, I took the turkeys to a local restaurant that I knew would prepare wild game. I asked them to do the turkeys Hawaiian-style, and they did not disappoint! The turkeys ended up as a delicious turkey tempura, among other things. Other Hawaiian turkey preparations include Turkey Katsu (Fried Cutlet with katsu sauce) and turkey lau lau, which is steamed in taro leaves. Bottom line, it was delicious, and one of the best wild game dinners I’ve ever had.

Overall, I highly recommend hunting in Hawaii should you ever find yourself there. Hawaii is not only the beach and the ocean, and hunting is a great way to enjoy a little more of everything Hawaii has to offer.

Much Mahalo to Hawaii Safaris for the excellent hunt, and to the excellent chef!

How Hawaii Squandered Its Food Security — And What It Will Take To Get It Back

Hawaii’s reliance on food imports began in the 1960s. To achieve self-sufficiency again, experts say it will take old values and new tools. –

By Brittany Lyte –

Nearly 2,500 miles from the nearest continent, Hawaii spends up to $3 billion a year importing more than 80% of its food — a dilemma that government leaders, economists, farmers, food shoppers and community activists have long tried to solve.

Things weren’t always so grim.

For centuries Native Hawaiians managed a self-sufficient agricultural system distinguished by thriving fishponds and taro, banana, pig, chicken and sweet potato production.

But with the arrival of Westerners, vast stretches of farmland were transformed into sprawling pineapple and sugar cane plantations that exploited cheap land and cheap labor to produce goods that were mostly shipped out of state.

By the 1960s, only about half of the state’s fruit and vegetable supply was produced locally — an important roadmark in the long decline of Hawaii’s food sovereignty. Researchers have found that an island needs to be growing at least 50% of its staple crops — foods like rice, ulu, potatoes, wheat — in order to be self-sufficient if disaster strikes.

The coronavirus pandemic, which raised the risk of shipping disruptions and stoked fears of food shortages, has only exacerbated the archipelago’s vulnerability.

To gain momentum toward the goal of reclaiming self-sufficiency, it’s helpful to examine what’s changed in the half-century since Hawaii last produced roughly half its food.

But as society looks to strengthen the state’s agricultural future, experts emphasize that Hawaii can’t simply revert back to the sustainable food system of the past.

“We’re not in the same environment,” said Noa Lincoln, assistant professor of indigenous crops and cropping systems at the University of Hawaii Manoa. “We have to deal with challenges that our ancestors didn’t have to — new species of weeds and pests and rodents and diseases that just didn’t exist.”

“Our ancestors developed their agricultural practices and methods in an environment that was really different,” he said. “And there’s literally no going back to that.”

But self-sufficiency in the 21st century will require a new system rooted in the sustainable values that guided Hawaii’s pre-Western food system, Lincoln said.

Overreliance On Imports Started In The 1960s

Although Hawaii’s sugar plantations reached peak production in the ‘60s, the decade also marked the start of their long decline.

Statehood in 1959 gave rise to workers’ rights, which raised plantation labor costs. Sugar and pineapple companies responded by moving their operations abroad. Thousands of acres of some of the most viable farmland was gradually lost to development to support a new tourism-based economy.

As plantations declined, diversified agriculture grew. But so did Hawaii’s reliance on food imports — a response to increasing demand by an emerging tourism sector that quickly usurped agriculture as the state’s economic engine.

Local agriculture could not keep up with the soaring needs for large and consistent quantities of food to supply hotels and other facilities.

To this day, the small-scale farms that make up the bulk of all farms across Hawaii struggle to achieve economies of scale. Roughly 87% of the 7,328 farms statewide generate less than $50,000 annually.

“One of the biggest issues is how hard it is to be a farmer in Hawaii — specifically to make money as a farmer,” said Angela Fa’anunu, a tourism professor at the University of Hawaii Hilo who farms breadfruit on 10 acres near Hilo.

What’s more, the inconsistency between county and state rules for agricultural activities can be difficult for farmers to navigate.

For example, although the Legislature adopted a state law to let farmers sell their farm products on agricultural land in 2012, some farmers have been unable to do so until recently due to conflicting county zoning rules.

“The systems in place, the policies themselves, limit the ability of a farmer to produce,” Fa’anunu said. “The policies themselves are meant to protect agricultural land, but they can be so restrictive that they make it really difficult for a farmer to just get something done.”

Farmers Need More Support, Incentives

More than food sovereignty, advocates claim Hawaii would reap many benefits from growing more food for local consumption: healthier diets, a deeper connection between nature and society, beautification of the landscape.

Replacing food imports with Hawaii-grown alternatives would also strengthen the island chain’s economy.

But the slow pace of progress has frustrated many farmers, citing challenges ranging from the high cost of land to zoning and infrastructure issues.

Many experts agree that more government support is needed to rejuvenate local food production.

The state created the Agribusiness Development Corp. in the early ‘90s to help map out a new plan for Hawaii’s agricultural future. Over the last three decades, the state has given the ADC nearly a quarter of a billion dollars.

But as a scathing report from the state auditor’s office pointed out earlier this year, the ADC has accomplished little. The state has never really figured out what its post-plantation agricultural system should be.

“To me, it’s depressing when I go into the grocery store and the ginger root is coming in from Brazil,” said Bruce Mathews, a professor of soil science at UH Hilo.

“And it isn’t better quality, but it (costs) so much less (money) than what people could sell it for if it was grown here locally. That’s why, without changing some of the policies here, I don’t see how we’re going to move the needle on local food production.”

Today less than 1% of the state budget is committed to agriculture, whereas the plantations that were so profitable in their heyday had the support of generous government incentives.

Reinstating agricultural tax breaks could be key to ratcheting up food security, Mathews said.

“If the state is serious about improving local food production, then we have to realize that most food around the world is to some extent subsidized,” Mathews said. “We have to make it more attractive for people to go into food production so that a person would think, ‘I’d rather go into farming than work at McDonalds.’”

To make that happen, Hawaii needs to invest in agricultural parks, irrigation systems and distribution facilities with the same gusto that it developed infrastructure and amenities to support tourism, said Glenn Teves, a University of Hawaii extension agent on Molokai who grows taro and tropical fruit on his 10-acre Hawaiian homestead farm.

“It’s not enough to make land available for agriculture,” Teves said. “If you’re serious about developing agriculture, you need to look at the big picture and create infrastructure similar to what was done for tourism: airport, convention center, hotels, scenic vistas.”

Community Opposition Slows Big Ag Production

Fierce community opposition to some proposed agricultural projects, such as dairy farms, is another significant hurdle, Mathews said.

On the Big Island, for example, residents were upset when they learned that a dairy had used GMO corn to feed the cows.

The dairy ultimately had to pay environmental fines after it was sued by a community group alleging that the owners violated the Clean Water Act after residents claimed to have found bacteria in brown water downstream from the facility.

The dispute ultimately put the Big Island dairy out of business.

On Kauai, a five-year effort to establish a dairy to reduce the state’s reliance on imported milk crashed and burned in part due to residents’ concerns over the possibility that the dairy could send foul odors and flies downwind to south shore beaches and hotel pools.

Environmental compliance and community pushback isn’t just a problem for dairy farmers, but for many kinds of large-scale agriculture projects in Hawaii, Mathews said.

“I feel that as we become a more suburban and urban society, we’ve become more eco-hypocritical or eco-imperialistic,” Mathews said. “In other words, we don’t want noise, pesticides, pollution in our own backyard — but we don’t mind so much paying for food imported from other places.”